If you’re struggling to get an accurate read on the economy, you’re not alone.

There are plenty of mixed signals out there. Nationally, inflation, high interest rates, and ongoing supply chain issues continue to make consumers and employers anxious. Add to that, concerns have swirled about a possible recession. Some sectors, like tech and media, saw significant layoffs, which could signal an economic slowdown.

Nonetheless, the job market is still roaring. That’s especially true in Massachusetts, where 3.4% unemployment in November bested an already low national rate of 3.7%.

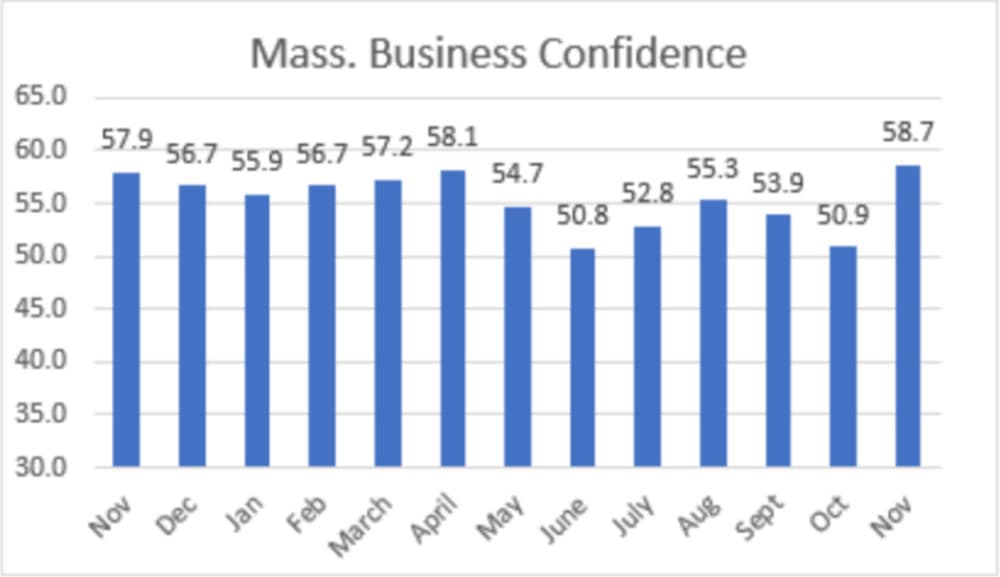

Employers in the state are also feeling OK. According to the most recent survey from the Associated Industries of Massachusetts, business confidence rose in November after a precipitous decline during the late summer and early fall.

WBUR asked some experts to share their thoughts about five top economic issues and what they may indicate for Massachusetts next year.

1. Housing: Mass. has about a quarter of homes needed for ‘healthy’ market

There’s no sugar-coating this: It’ll be another tough year for those looking to buy a home in Massachusetts.

The interest rate for the average 30-year mortgage has nearly doubled since last year. For a $500,000 mortgage, that means an increase of nearly $1,000 per month on payments. As of October, the median price of a single-family home in Massachusetts was $520,000, according to the real estate data site The Warren Group.

On top of that, buyers won’t find much relief on home prices, according to projections from the state realtors’ association.

“We’re really not seeing that price adjustment, I think simply because inventory is so remarkably low right now,” said David McCarthy, incoming president of the Massachusetts Association of Realtors.

Low inventory means buyers are still competing with one another. McCarthy said realtors continue to see multiple offers for some properties.

According to McCarthy’s organization, Massachusetts has just 26% of the housing inventory typically found in a “healthy,” or more balanced, real estate market.

Housing experts say the anemic supply is, in large part, a result of restrictive zoning in many communities.

In Boston, the dearth of housing has been a sticking point for residents and lawmakers. It’s an issue Mayor Michelle Wu has indicated she wants to tackle. Wu has made significant personnel changes on the city’s Zoning Board of Appeals in hopes of capturing a wider range of perspectives on the matter. Housing experts say zoning rules are a key factor in determining housing stock. Other factors include construction costs and the number of owners putting their homes on the market.

There is at least some evidence housing construction is on the rise. More housing permits were issue in 2021 than in any year since 2005, according to a report from the Boston Foundation.

Last year, Gov. Charlie Baker’s administration directed municipalities to build more multi-family units around MBTA stations. Wu has also signaled plans to increase affordable housing stock in Boston.

But it may take years before it’s known whether these policies help ease the housing crunch, said Dawn Ruffini, outgoing president of the state association of realtors. Meanwhile, Ruffini said the state’s initiative to build more housing is already getting pushback in some communities. A group of citizens in Rockport, for example, filed a lawsuit against Baker’s directive calling it “unconstitutional.”

“The hardest part is when you hear people in the community who are complaining about how expensive it is to live there, and then in the same breath they’re at the town meeting slamming down and blocking development,” Ruffini said. “That is the definition of insanity right there.”

2. Tech: Hiring is strong but may slow down

Several prominent tech companies went through layoffs this year, including local firms, such as Starry Inc., Whoop and iRobot. Massachusetts outposts of Twitter and Amazon also experienced layoffs.

The moves created some unease in an industry that employs 8.5% of the state’s workforce.

Christopher Anderson, president of the Massachusetts High Technology Council, a trade group, said tech leaders and investors wary of economic trends are spending more conservatively.

“We’re not surprisingly seeing the impact of headwinds that are a combination of an impending recession,” he said, and rising costs of labor and supplies.

Anderson doesn’t think layoffs spell disaster for the state’s tech industry. While job postings declined slightly from a few months ago, he said the demand for tech talent still outweighs the supply.

Anderson worries that in the next few years, tech companies will hire more workers outside Massachusetts, particularly from states with a lower cost of living and thus, lower salaries.

Scott Rankin, global head of strategy at the accounting company KPMG International, expects to see more layoffs in 2023. He pointed to tech companies as a possible harbinger for the broader economy.

“Tech typically leads into a downturn and is impacted first,” he said, and that “cascades its way through the economy.”

A slower tech market could have some silver linings, according to Rankin. Tech companies are likely to shift their focus away from rapid growth in favor of more targeted, long-term investments.

A gentle economic slowdown could give some startups more breathing room to build their businesses — and compete with tech giants, especially when it comes to recruiting and hiring workers.

3. Workforce: Shrinking numbers signal a slowdown

For economic researchers, observing demographic data is about as close as they can get to looking into a crystal ball. Trends in births, deaths and migration can hint at what the future economy may look like.

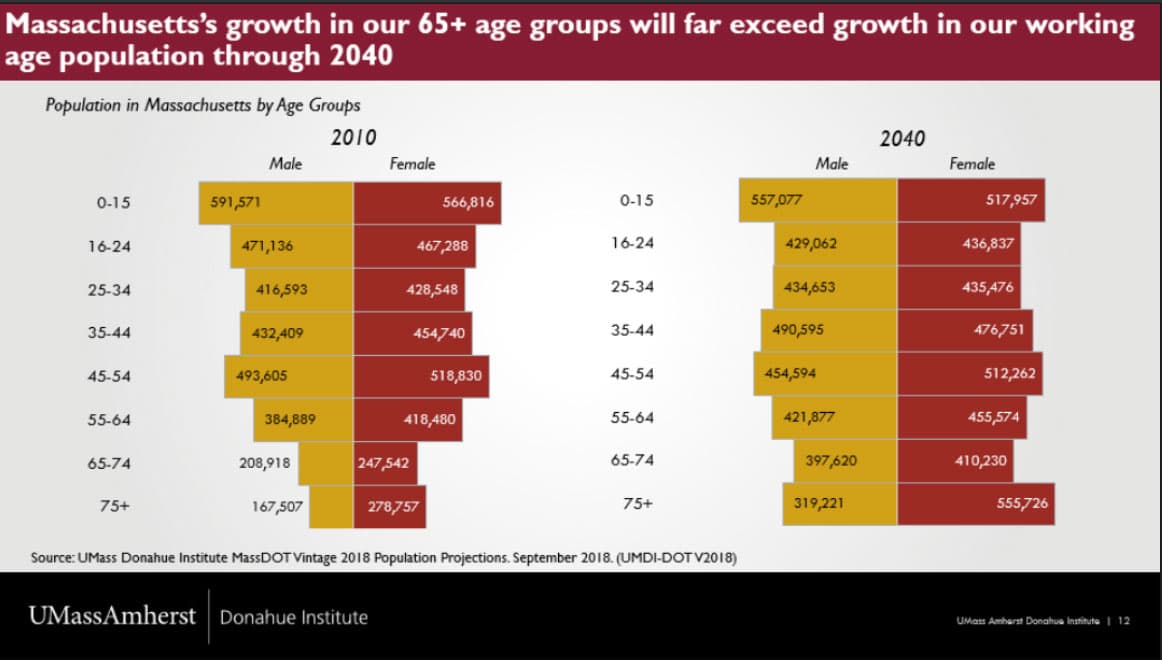

In Massachusetts, these trends point to slower economic growth, said Mark Melnik, director of economic and public policy research at the UMass Donahue Institute.

Melnik said the pandemic accelerated shifts in the state’s workforce. Currently, people 65 and older make up 13% of the Massachusetts population. In 2050, that number will be closer to 25%, he said. These residents are more likely to retire or reduce their work hours, which reduces the size of the overall workforce.

As the pandemic wore on in 2021, Melnik said he noticed a common narrative that people were opting out of jobs, leaving employers without enough workers. But he said that wasn’t the full story. “What was really happening was the labor force was just smaller in Massachusetts than it was pre-pandemic,” Melnik said, adding that more baby boomers retired and left a gap in the market.

Another worrying trend economists are flagging: More people have been leaving the state. Between July 2020 and July 2021, Massachusetts lost an estimated 46,000 residents. More recent data indicates the state keeps losing more residents than it gains.

The outflow of people compounds the problem of a shrinking workforce. Melnik said one of the most important efforts the state can make to curb an economic slowdown is to focus on raising employment rates among so-called “hidden workers” — a term that means populations with lower participation rates in the workforce. That includes formerly incarcerated residents, veterans, people with disabilities and people without a high school diploma.

“Aside from it being a moral obligation to try to help these populations be better engaged in the labor market, it’s going to be a necessity for businesses in the state to find labor in places where they maybe weren’t able to before,” Melnik said.

4. Labor: Gains reflect momentum

Over the last decade, union membership has hovered around 12% of all Massachusetts workers. But according to data from the National Labor Relations Board, 101 union petitions were filed in the state in 2022 — a 240% increase compared to 2021.

Darlene Lombos, executive secretary treasurer of the Greater Boston Labor Council, said lessons learned during the pandemic increased support for unions.

“Workers are really seeing that they deserve more, and they’ve always deserved more,” she said.

Many Massachusetts workers participated in national efforts to unionize big corporations. Of the dozens of union petitions filed in the state this year, about 20 were at Starbucks stores. The largest filings, representing thousands of workers, were on behalf of graduate students at Boston University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Lombos said she’s also been working to unionize the growing cannabis industry in Massachusetts.

Meanwhile, Lombos said trade unions are increasing apprenticeship programs, particularly for women and people of color, in part thanks to nearly $2 billion in federal infrastructure funding.

“That is one of the most incredible opportunities to grow our movement,” Lombos said.

5. Food and retail: High costs eat into profits

For restaurants and retail, rising supply and labor costs have cut into already thin profit margins.

But Stephen Clark, president of the Massachusetts Restaurant Association, said the holiday season was solid for the industry. He said it’s a good sign for retailers that corporate and holiday parties have made a comeback after a couple years of COVID-prompted cancellations.

“It’s certainly getting better,” Clark said.

Clark also noted that the restaurant business is undergoing a lot of changes. In addition to offering more takeout and adding new technology, many establishments are curtailing operating hours. Gone is the old mindset that eateries need to be open all the time, Clark said.

“There’s been a lot of effort [toward] maximizing the profitable times,” he said. “And I don’t think that’s going to go away.”

For Massachusetts retailers, sales were up for the year an average of 6% compared to 2021, according to Jon Hurst, president of the Retailers Association of Massachusetts. The trade organization represents 4,000 retailers statewide.

But higher sales numbers don’t necessarily translate to higher profits.

“Sales dollars may be up simply because your prices are higher, but your actual transactions are down,” Hurst said.

Hurst added that spending slowed down during several weekends in the fourth quarter of 2022, which may signal lower consumer confidence going into 2023.

“The savings that [consumers] accumulated through the pandemic are gone by a large measure,” he said “And, of course, they’re seeing the higher prices of even just common everyday goods.”

The interactive graphic above that displays Massachusetts tech job postings is courtesy of the Massachusetts High Technology Council.

link

More Stories

NLCU: Navigating the Affordable Multi-Family Housing Development Process

FHLBank Atlanta Announces New Affordable Housing Advisory Council Members

Middlebury College, developer and town join forces on major housing project